+++ for English, see below +++

Für gewöhnlich fragen wir uns ja eher, was gerade um Himmels Willen im Kopf des Redners vorgeht, den wir gerade dolmetschen. Unsere Kollegin Eliza Kalderon jedoch stellt in ihrer Doktorarbeit die umgekehrte Frage: Was geht eigentlich in den Dolmetscherköpfen beim Simultandolmetschen vor? Zu diesem Zweck steckt sie Probanden in die fMRT-Röhre (funktionale Magnetresonanztomographie), um zu sehen, was im Gehirn beim Dolmetschen, Zuhören und Shadowing passiert. Und so habe auch ich mich im November 2014 aufgemacht an die Uniklinik des Saarlandes in Homburg. Nachdem uns dort Herr Dr. Christoph Krick zunächst alles ausführlich erklärt und ein paar Zaubertricks mit dem Magnetfeld beigebracht hat (schwebende Metallplatten und dergleichen), ging es in die Röhre.

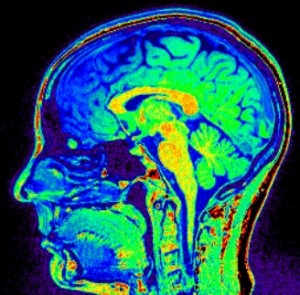

Dort war es ganz bequem, der Kopf musste still liegen, aber die Beine hatten zu meiner großen Erleichterung viel Platz. Dann habe ich zwei Videos im Wechsel gedolmetscht, geshadowt und gehört, ein spanisches ins Deutsche und ein deutsches ins Spanische. Neben dem Hämmern der Maschine, das natürlich ein bisschen störte, bestand für mich die größte Herausforderung eigentlich darin, beim Dolmetschen die Hände stillzuhalten. Mir wurde zum ersten Mal richtig klar, wie wichtig das Gestikulieren beim Formulieren des Zieltextes ist. Nach gut anderthalb Stunden (mit Unterbrechungen) war ich dann einigermaßen k.o., bekam aber zur Belohnung nicht nur sofort Schokolade, sondern auch direkten Blick auf mein Schädelinneres am Computer von Herrn Dr. Krick.

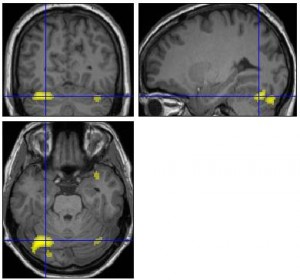

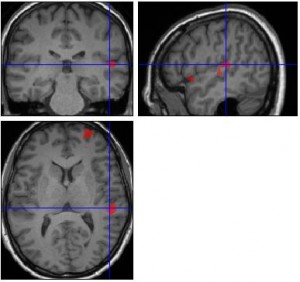

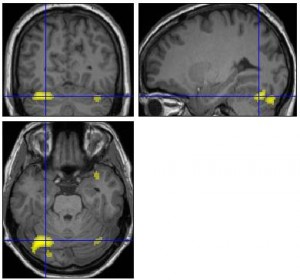

Natürlich lassen sich bei einer solchen Untersuchung viele interessante Dinge beobachten. Beispielhaft möchte ich zum Thema Sprachrichtungen Herrn Dr. Krick gerne wörtlich zitieren, da er mir das Gehirngeschehen einfach zu schön erläutert hat: “Da Sie muttersprachlich deutsch aufgewachsen sind, ergeben sich – trotz Ihrer hohen Sprachkompetenz – leichte Unterschiede dieser ähnlichen Aufgaben bezüglich sensorischer und motorischer Leistungen im Gehirn. Allerdings möchte ich nicht ausschließen, dass der Unterschied durchaus auch an der jeweiligen rhetorischen Kompetenz von Herrn Gauck und Herrn Rajoy gelegen haben mag … Wenn Sie den Herrn Gauck ins Spanische übersetzt hatten, fiel es Ihnen vergleichsweise leichter, die Sprache zu verstehen, wohingegen Ihr Kleinhirn im Hinterhaupt vergleichsweise mehr leisten musste, um die Feinmotorik der spanischen Sprechweise umzusetzen.”

“Wenn Sie aber den Herrn Rajoy ins Deutsche übersetzt hatten, verbrauchte Ihr Kleinhirn vergleichsweise weniger Energie, um Ihre Aussprache zu steuern. Allerdings musste Ihre sekundäre Hörrinde im Schläfenlappen mehr sensorische Leistung aufbringen, um den Ausführungen zu folgen. Dies sind allerdings nur ganz subtile Unterschiede, die in der geringen Magnitude den Hinweis ergeben, dass Sie nahezu gleich gut in beide Richtungen dolmetschen können.”

Dies ist nur einer von vielen interessanten Aspekten. So war beispielsweise auch mein Hippocampus relativ groß – ähnlich wie bei Labyrinth-Ratten oder den berühmten Londoner Taxifahrern … Welche wissenschaftlichen Erkenntnisse sich aus der Gesamtauswertung der Studienreihe ergeben, dürfen wir dann hoffentlich demnächst von Eliza Kalderon selbst erfahren!

PS: Und wer auch mal sein Gehirn näher kennenlernen möchte: Eliza sucht noch weitere professionelle Konferenzdolmetscher/innen mit Berufserfahrung, A-Sprache Deutsch, B-Sprache Spanisch (kein Doppel-A!), ca. 30-55 Jahre alt und möglichst rechtshändig. Einfach melden unter kontakt@ek-translat.com

PPS: Auch ein interessanter Artikel zum Thema: http://mosaicscience.com/story/other-words-inside-lives-and-minds-real-time-translators

+++

Normally, we rather wonder what on earth is going on in the mind of the speaker we are interpreting. Our colleague Eliza Kalderon, however, puts it the other way around. In her phD, she looks into what exactly happens in the brains of simultaneous interpreters. To find out, she puts human test subjects into an fMRI machine (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) and monitors their brains while interpreting, listening and shadowing. I was one of those volunteers and made my way to the Saarland University Hospital in Homburg/Germany in November 2014. First of all, Dr. Christoph Krick gave us a detailed technical introduction including a demo of how to do magic with the helfp of the magnetic field (flying metal plates and the like). And then off I went into the tube.

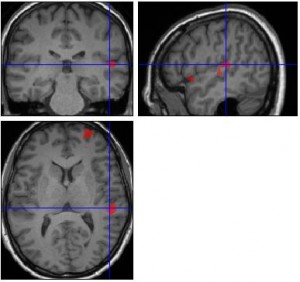

To my delight, it was quite comfortable. My head wasn’t supposed to move, ok, but luckily my legs had plenty of room. Then Eliza made me listen to, interpret and shadow two videos: one from German into Spanish and one from Spanish into German. The machine hammering away around my head was a bit of a nuisance, obviously, but apart from that the biggest challenge for me was keeping my hands still while interpreting. I hadn’t realised until now how important it is to gesture when speaking. After a good one and a half hour’s work (with little breaks), I was rather knocked out, but I was rewarded promptly: Not only was I given chocolate right after the exercise, I was even allowed a glance at my brain on Dr. Krick’s computer.

There are of course a great many interesting phenomena to observe in such a study. To describe one of them, I would like to quote literally Dr. Krick’s nice explanation: “As you have grown up speaking German as a mother tongue, despite your high level of linguistic competence, we can see slight differences between the two similar tasks in terms of sensoric and motoric performance in your brain. However, it cannot be ruled out that these differences might be also be attributable to the respective rhetorical skills of Mr. Gauck and Mr. Rajoy. When translating Mr. Gauck into Spanish, understanding involved comparably less effort while the cerebellum in the back of your head had to work comparably harder in order to articulate the Spanish language.”

“When, on the other hand, translating Mr. Rajoy into German, your cerebellum needed comparably less energy to control your pronunciation. Your secondary auditory cortex, located in the temporal lobe, had to make a greater sensoric effort in order to understand what was being said. Those differences are, however, very subtle, their low magnitude actually leads to the assumption that you practically work equally well in both directions.”

This is only one of many interesting aspects. Another one worth mentioning might be the fact that my hippocampus was slightly on the big side – just like in maze rats or London cab drivers … I am really looking forward to getting the whole picture and reading about the scientific findings Eliza draws once she has finished her study!

PS: If you, too, would like to get a glimpse inside your head: Eliza is still looking for volunteers! If you are a professional, experienced conference Interpreter with German A and Spanish B as working languages (no double A!), about 30-55 years old and preferably right-handed, feel free to get in touch: kontakt@ek-translat.com

PPS: Some further reading: http://mosaicscience.com/story/other-words-inside-lives-and-minds-real-time-translators

PPPS: A portuguese version of this article can be found on Marina Borges’ blog: http://www.falecommarina.com.br/blog/?p=712

Leave a Reply