As Mandarin Chinese interpreters, we understand that we are somewhat rare beings. After all, we work with a language which, despite being a UN language, is not one you’d encounter regularly. We wouldn’t expect colleagues working with other, more frequently used languages to know about the peculiarities of Mandarin.

This applies not least to terminology tools. Many of the tools available to interpreters do now support Chinese-script entries. And indeed: Interpreting from English into Chinese, terminology software works as well for Chinese as it would for any other language – next to good old Excel, I myself have used InterPlex, Interpret Bank and flashterm. It’s rather when working from Chinese into English that things get tricky – and that’s not necessarily a software issue.

Until recently, many interpreters were convinced and rather adamant that simultaneous interpreting with Chinese is downright impossible, and I am sometimes tempted to agree. Compared to English – left alone German – Chinese is incredibly dense. Many words consist of only one syllable, and only very few of more than two. Owing to the way Chinese works grammatically, the very same idea can be expressed a lot more concisely in Chinese than English. To make matters worse, we replace modern Mandarin expressions with written, Classical Chinese equivalents in formal Mandarin. As a rule of thumb, the more formal the Chinese used, the more succinct it will be as well – rather different from English or German. This also is the case with proper names and terminology, which will usually have abbreviated forms that are a lot shorter syllable-wise than their English equivalents.

Adding to that, Chinese natives are incredibly fond of their language and make ample use of its full range of options: Using rare and at times byzantine expressions and words is appreciated and applauded as a sign of good education; it is never perceived as pedantic or conceited. This includes idioms (chengyu 成語), which usually refer to a story from the Chinese Classics in a highly condensed fashion: They generally contain a mere four syllables and usually function as adjectives, in contrast to English or German. In English, we will need at least a full sentence to explain what is being said, even if the same or a similar idiom exists. Chinese also frequently uses xiehouyu 歇後語: proverbs consisting of two parts, the first presenting a scenario, the second outlining the rationale of the story. Usually, the second part will be left out because Chinese natives will be able to deduce it from the first – similar to speak of the devil (and he will appear) in English. Needless to say, there hardly ever is an English equivalent, and seeing that we are operating in entirely different cultural contexts, ironing out cultural differences when explaining xiehouyu will take additional time.

It will be no surprise to hear that Chinese discursive and grammatical peculiarities make it a difficult language to interpret from: relative clauses tend to be lengthy – and are always placed in front of the noun they describe; Chinese doesn’t mark tenses as such but rather uses particles to outline how different events and actions relate to each other, in contrast to linear notions of time and tenses in European languages, so we are often left guessing; he and she are homonyms in Mandarin; to name but three examples.

Considering all of this, we see that more often than not, simultaneous interpreting from Chinese is a race against the clock and an exercise in humility – and there isn’t much time to look up words in the first place.

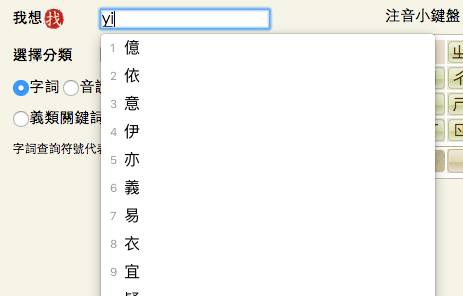

In Modern Mandarin, there are only around 1,200 possible syllables, with each syllable being a morpheme, i.e. a component bearing meaning; in English, we have a far greater range of possible syllables, and they only make sense in context, as not every syllable carries meaning: /mea/ and /ning/ do not mean anything per se, but meaning does. For Chinese, this implies that homophones are a common occurrence. And while we aim for perfect clarity and lucidity in English, Chinese rather daoistically indulges in ambivalence. Clever plays on words, being illusive and vague and giving listeners space to interpret what you might actually mean: not bad style, but an art to be honed. Apart from having to spend more capacity and time on identifying terms and words used in the original, this adds another layer of difficulty with regards to looking up terminology in the booth: The fastest way to type Chinese characters is by using pinyin romanisation, but owing to the huge number of homonyms, any syllable in romanized transliteration will give you a huge range of options. This means that we would have to spend at least another second or so simply to select the correct character from a drop-down list – and we will not enjoy the pleasure of word prediction that works for other languages.

In practice, this means that besides very intensive preparation before the event, we rely on what might be the oldest terminology tool in the world: our booth buddy. They are particularly important because in Chinese, we obviously don’t have any cognates – something than might get us off the hook working with European languages. We also heavily rely on our colleagues sitting next to us for figures: Chinese has ten thousand (萬) and one hundred million (億) as units in their own right, so rather than talking about one million and one billion, the Chinese will talk about a hundred times ten thousand and ten times one hundred million, respectively. This means we will have to be calculating while interpreting: a feat hard to accomplish if you are out there on your own.

While I started out thinking that not being able to use terminology software to the same extent I would use it for German-English would be quite a nuisance, I have found that this is rather an instance of the old man living at the border whose horse runs away1, as you’d say in Chinese. Interpreting is teamwork after all, and working with Chinese, we are acutely aware that we rely on our booth buddy as much as they rely on us and that we can only provide the excellent service we do with somebody else in the booth. With that in mind, professional Chinese interpreters always make for great partners in crime in the booth.

About the author:

1 (which, as the story goes, then returns, bringing a fine stallion with it, which is then ridden by his son, who falls of the horse and breaks his leg, which is why he is not drafted and sent to war, ultimately saving his life; meaning that any setback may indeed be a blessing in disguise, similar but not entirely identical to every cloud has a silver lining. One of the most frequently used Chinese sayings, eight syllables of which the latter four are generally left out: 塞翁失馬,焉知非福, which literally translates as ‘When the old man from the frontier lost his horse, how could one have known that it would not be fortuitous?’. I rest my case.)

Leave a Reply