Cognitive sustainability

Flight-shaming, banning fast fashion, upcycling old milk cartons, taking financial precautions for when we are old or a pandemic strikes – it’s sustainability all around. But what about our most precious working resource – our brain? Is “cognitive sustainability” a thing at all?

Sustainability

There are many definitions of sustainability. Although originally coined as an ecologic concept, the subject is nowadays discussed from many perspectives, such as the ecological, economic, or social one, and usually on a collective level, looking at our planet, the economy, society as a whole. Cognition, in contrast, is rather individual in nature. For our purpose as knowledge workers, being sustainable could be defined as maintaining a system or level of performance in the long run without damaging or depleting resources, i.e. not exploiting them.

Cognition

Cognition is generally understood to be the totality of processes and structures of information handling in an intelligent system or – in humans – of mental activity, as well as their results. It includes information acquisition, processing, and storage with their different sub-activities (see below).

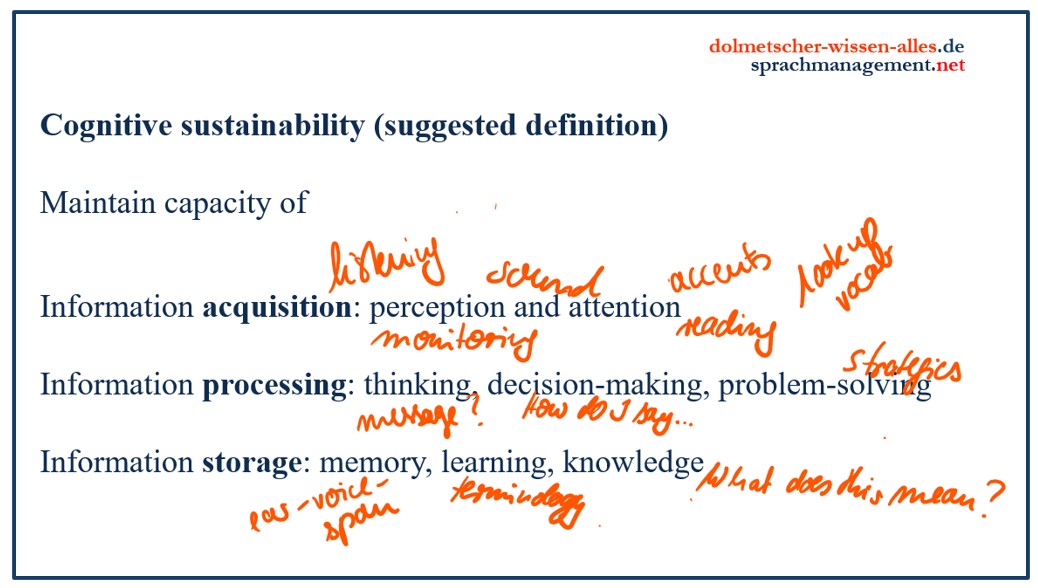

Cognitive sustainability (suggested definition)

For the purpose of knowledge work, and conference interpreting in particular, the following definition of cognitive sustainability could thus be formulated:

The long-term preservation of (individual/collective) capacities of

- Information acquisition: perception and attention

- Information processing: thinking, decision-making, problem-solving

- Information storage: memory, learning, knowledge

And now, the different sub-activities of simultaneous interpreting (and consecutive interpreting, for that matter) fall into place very nicely. Information acquisition involves not only listening to the source speech, including compensating for poor sound quality, hard-to-understand accents, etc., but also watching the speaker and reading supplementary information (texts, glossaries, presentations), monitoring one’s own output, dividing one’s attention between the various sources of information and forcing oneself to concentrate even under difficult conditions, such as high speed and fatigue.

Information processing is about understanding and temporarily storing the message while simultaneously producing the target text, which involves countless micro-decisions (“How do I say this?”) and the use of strategies in problematic situations (“Should I summarise redundancies? Do I explain a culture-specific particularity or acronym? Say Du or Sie in German/tú or usted in Spanish? Use gender-inclusive language?”).

In terms of information storage, things get really interesting in interpreting: short-term memory plays a fundamental role in controlling the delay between the original and the interpreted speech (décalage), while linguistical, contextual, and situational knowledge is continuously retrieved from the long-term memory. In terms of cognitive sustainability, the question of whether terminology and semantic knowledge acquired for a specific assignment can be recalled in the heat of the moment and how much knowledge from one interpreting job “sticks” in our memory and can be reused for future assignments is particularly interesting.

So now, what does that mean in practice?

While I was thinking and reading about these definitions, countless things sprang to my mind that we can do to preserve our cognitive capacities.

Be nice to your body AND mind

I’d been trying to think of an analogy regarding cognitive load in simultaneous interpreting for quite some time, when finally, an idea came to my mind when I was least thinking about it (as we know, our minds continue to work on unsolved problems in the background, whether we want it or not). Normally I am not too enthusiastic about comparing the brain with “the rest” of our body, but in this case I really like the picture: The physical exercise that comes closest to simultaneous interpreting seems to me the so-called High Intensity Interval Training. While doing HIIT, not in my dreams would it occur to me to do a few push-ups in the 20-second rest period between a round of jumping jacks and a sequence of squats. It’s perfectly clear that I’m busy just breathing and saving my energy for the next round. In the booth, however, in the middle of an interpreting assignment, it is not quite as obvious to me to close my eyes in the breaks and let my brain go idle (let alone go and get some fresh air) before it is my turn again. There are just so many things that can be done in those intervals between the high-intensity phases of simultaneous interpreting! Helping our colleague, of course – but then also preparing manuscripts, writing emails, reading the newspaper. Or popping out to get some coffee and biscuits, especially in the afternoon when we are starting to get exhausted, and our brains crave glucose. This doesn’t really bring my speed or concentration back to pre-exhaustion level, and I won’t remember a lot of what is being said by tomorrow, but I have really managed to get things done. Not very sustainable, now you mention it.

And then, one Friday morning, after a good week’s work, I tried to think of a way to get this message across. But my brain just wouldn’t come up with anything meaningful, and I couldn’t bring myself to sit at my desk and draw up another PPT presentation either. So I decided simply to give in to what my body and mind were telling me they needed (aka displacement activity) and created a little video instead. It brings the message across efficiently (and I hope sustainably) in 18 secs even to generation Tiktok, plus I had some fun creating it.

And what else can we do? Here are some ideas:

Be energy-efficient: manage the duration and intensity of your tasks

- Interruptions can be good or bad. So-called displacement activities exist for a reason (divert mental attention and physical energy, cut off stress temporarily), so you may as well be mindful and notice when it is time for a good break, which helps you recover and relax. You can concentrate on a task of high cognitive load for a certain time, until you notice your mind – or your body – starts to wander. You may also set your alarm to 15-30 minutes. Then do nothing or something mentally undemanding but – to the extent possible – fulfilling (watering flowers, feeding birds/cats/dogs/kids/husband/wife, sorting documents, painting toenails). Also give your mind a break while in the booth, and take turns when you feel you need a break.

- Avoid bad, i.e., external interruptions that get you out of your workflow. Mute your phone, doorbell, family, etc. as far as socially acceptable 😉

- Switch between high and low cognitive load during deskwork (concentrated reading and understanding technical content/extracting terminology vs. looking up equivalents/renaming and sorting files, writing invoices etc.). Information will then be more likely to be stored as knowledge in your long-term memory. It’s a bit like heating a house: While the heating is on, you better keep the windows shut to keep the heat inside and not to waste energy. You only open the windows shortly once in a while – preferably with the heating turned off – to get some fresh air.

- Know the effects of pro- and precrastination (Huberman’s Duration-Path-Outcome (DPO) model can also be helpful)

- Research suggests that there is no such thing as multitasking. We only task-switch. Actually, we get more things done within the same time if we do one task after the other. Multitasking can also impair memory performance.

- Be aware of decision fatigue when organising your daily work. For example, try to do decision-intensive tasks in the morning.

- Self-disciplining to remain focused also requires cognitive effort.

- Routines and habits reduce cognitive load sustainably.

Intelligent knowledge investments – know the cognitive cost & don’t waste your capacities

- Knowledge is more “costly” to acquire than information (know the difference!), but it is easier to access and reuse. So it may be helpful to make strategic decisions as to which vocabulary to learn by heart and reuse in future conferences and which not, and which subjects to familiarise yourself with.

- One essential feature of information is that it is relevant (i.e., needed at a certain moment to solve a problem or fill a knowledge gap). Things we find relevant are also easier to remember. It therefore makes much more sense to look up things right in the moment when they are needed, rather than three days later (no more post-conference follow-up).

- Eliminate “noise”, i.e., useless information (rather read a few good newspaper articles or listen to select radio reports instead of scrolling through the news five times a day; subscribing to specific newsletters/blogs may be more informative than reading social media, listening to the radio and podcasts only when you really want to pay attention; create terminology shortlists instead of learning 200 terms in 10 minutes). What information do I really need, what will still be useful the day after tomorrow?

- Cognitive overload and lack of sleep prevent knowledge from entering long-term memory.

- Talking helps information to make its way to your long-term memory. Discussing tricky terminology or complicated technical issues in the morning always helps me to dive deeper into the subject at hand.

Filtering & Sorting – recycle the assets you have

Categorise and tag your terminology by client, topic, or importance so that you can selectively filter out and “recycle” the terminology you already have in your database or glossary. When looking up your odontology vocab from last year’s press conference, your episodic memory may also kick in, helping you remember what was discussed back then, linking it to the job you are preparing for right now. Shortlisting and prioritising also help to have essential terminology, names, acronyms etc. for a certain customer or conference available within seconds. Minimalistic and highly relevant information based on your personal experience – you can hardly get any more sustainable!

Digital offloading and automation

Outsourcing tasks to a computer means offloading “worthless“ activities (typing words, looking up very basic words, term extraction) so as to free up cognitive capacities for the more important mental tasks (comprehension, memorising). Again, a matter of weighing the options and priorities. Not every fancy tool really has an added value, and not everything can be offloaded to a machine. Some skills just can’t be delegated to machines (yet?), and some knowledge must be retrievable at any time without delay.

Storing data sustainably

Obviously, data storage has nothing to do with cognition. But if managed smartly, the right file management helps keep the results of your cognitive effort or even just valuable information available in the long run. For example, portable file formats (csv, pdf/a, xml, txt, tif/jpg, mp3) reduce dependency on a particular software (unlike the user lock-in in the case of Kindle books, for example). CSV tables, for instance, can be opened and edited in an infinity of programs and moved back and forth between apps easily, which is great for sharing glossaries. Accordingly, working with very generic, widely-used programs like Microsoft Word or Excel makes your data relatively future-proof. Rather specific programs, e.g. terminology-management systems designed for the purpose of conference interpreters like InterpretBank, InterpretersHelp, or Interplex, often have much more to offer in terms of functionality and comfort. Luckily, they are often also compatible with generic programs, so that files can be exchanged using the import and export function.

Collaborative dossiers to prepare faster & better

Preparing in a shared online team file reduces the workload for everyone involved, to begin with. Furthermore, it has the enormous advantage that if you are preparing a text for the rest of the team, you are likely to do your research more thoroughly, because you know that others will rely on your work, be it terminology or background information. When colleagues discuss and comment on things in an online glossary, this communication and the emotional involvement lead to deeper processing, apart from it simply being fun. And that brings us full circle: cognitive sustainability indeed has a – very nice – collective dimension.

About the author:

Anja Rütten is a freelance conference interpreter for German (A), Spanish (B), English (C), and French (C) based in Düsseldorf, Germany. She has specialised in knowledge management since the mid-1990s.

Resources

Ariga, A. & Lleras, A. (2011) ‘Brief and rare mental “breaks” keep you focused: Deactivation and reactivation of task goals preempt vigilance decrements’, Cognition, 118(3), 439-443, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2010.12.007.

Barnet, Max (2020) How to Study & Tackle Assignments When You Don’t Want to (genei.io). https://www.genei.io/blog/how-to-study-and-tackle-assignments-when-you-dont-want-to?utm_campaign=Research+Tips+&utm_medium=email&utm_source=autopilot&genei_segment_id=da19b84f-cc0f-4d99-86be-f7e6922dd372

Barzon (2018) “Cognitive sustainability in Digital Experiences”. https://www.spindox.it/en/blog/cognitive-sustainability-digital/ (Taschenrechnereffekt).

Bates, S. (2018) ‘A decade of data reveals that heavy multitaskers have reduced memory, Stanford psychologist says’, Stanford News, 25th October, url: https://news.stanford.edu/2018/10/25/decade-data-reveals-heavy-multitaskers-reduced-memory-psychologist-says/. (We don’t multitask. We task switch.)

Bateson, G. (1972) Steps to an ecology of mind, New York: Ballantine Books.

Bruni, L.E. (2015) ‘Sustainability, cognitive technologies and the digital semiosphere’, International Journal of Cultural Studies, 18(1),103-117.

Cognitive Load Theory: http://www.elearning-psychologie.de/cl_clt_i.html

Döring, Ralf und Konrad Ott (2001): Nachhaltigkeitskonzepte. In: Zeitschrift für Wirtschafts- und Unternehmensethik 2 (2001)3. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-347600

Kluwe, Rainer H. https://www.spektrum.de/lexikon/psychologie/kognition/7882.

Kurzban, Robert, Angela Duckworth, Joseph W. Kable, and Justus Myers (2014): An opportunity cost model of subjective effort and task performance. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3856320/. (https://www.zeit.de/gesundheit/2022-09/geistige-erschoepfung-gehirn-glutamat-forschung/komplettansicht)

Mathers, Luke (2022) Curious Habits: Why we do what we do and how to change. Major Street Publishing

Stangl, Werner (2023): Kognition – Online Lexikon für Psychologie & Pädagogik. Wien-Linz-Freiburg 2023 https://lexikon.stangl.eu/240/kognition.

Uncapher, M.R. & Wagner, A.D. (2018) ‘Minds and brains of media multitaskers: Current findings and future directions’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(40), 9889-9896.

Contents

Leave a Reply